“The world is full of complainers. An' the fact is, nothin' comes with a guarantee. Now I don't care if you're the Pope of Rome, the President of the United States or Man of the Year, something can all go wrong. Now go on ahead, ya know, complain, tell your problems to your neighbor, ask for help, 'n watch 'im fly. Now, in Russia, they got it all mapped out so that everybody pulls for everybody else... that's the theory, anyway. But what I know about is Texas, an' down here... you're on your own.”

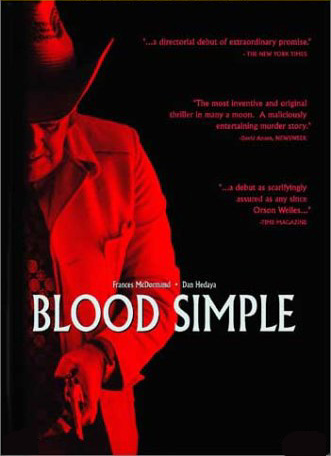

The film begins with melancholic, almost rueful, narration, visually matched with shots of a long, barren and desolate Texas road. Later, characters will dwell underneath ominous ceiling fans, which seem to hauntingly view down upon the hapless. The camera, fluid but controlled, focuses on doors, particularly at nighttime, heightening the palpable fear of who or what is lurking behind them. A blade of light slicing through the darkness underneath a door is snuffed out. An emphasis on the patulous Texas outdoors pervades the film, contrasted and juxtaposed with the stifling, closed interiors in which people struggle. Shots of cowboy boots populate much of the picture. Blood is found on the ground with great regularity. Otherwise decent people make highly unfortunate decisions. An otherworldly creature mercilessly stalks his prey. This, however, is not No Country for Old Men but rather Blood Simple, the 1984 film debut for Joel and Ethan Coen.

Blood Simple is a subtly mind-bending neo-noir crime thriller in which communication is hampered by circumstance and refuge is denied by the apparent intervention of fate. The picture, photographed with blue-tinted deliriousness by Barry Sonnenfeld, is laced with an oneiric imperishability of location and personage, which meticulously creates a moony pattern that courses through the picture—and the Coen oeuvre entire. Characters move through the film like stationary objects pushed, as they are compelled to vacate their respective natural habitats. As will be proven true with their later efforts, Blood Simple demonstrably essays the Coens' obsessions and idiosyncrasies, their fixations and concerns. As a debut, the film is as pure and distilled an introductory declaratory statement as any before or since.

After the film's dry, almost supernatural opening narration, Blood Simple brings its perspective, literally, with Ray and Abby (John Getz and Frances McDormand) driving at night. The road is visible again, and “The Road” will remain a recurring Coen motif. Abby's first line informs where the picture's plot is headed: her possessive husband gave her a .38 handgun as a gift, but she fears she would use it on him if she did not leave him. The camera remains behind Ray and Abby, he behind the steering wheel of his car, she in the passenger seat. The windshield is spattered with rain, which is furiously flung off by the windshield wipers. With each passing car's briefly blinding headlights moving past them, the main cast members have their names flash against the black of night in cool blue.

The Coens' penchant for quirky, offbeat humor—here typically slathered atop the film's laconic dialogue—makes Blood Simple less familiar than its superficially derivative story would suggest. Rooted in the work of James M. Cain, Jim Thompson and other authors of stories about lust and murder, Blood Simple takes on a twisted viewpoint characterized by mordant humor and razor-sharp wit. As Abby's husband, owner of the bar at which Ray works, Julian Marty (Dan Hedaya), confronts Ray in the back of the bar, the Coens use a bug-zapper to simultaneously underline and subvert Marty's dramatic lines. “You think I'm funny, I'm an asshole? No, no, no... what's funny is her... what's funny is, I had you two followed because if it's not you she's sleeping with, it's somebody else... what's funny is when she gives you that look and says, 'I don't know what you're talkin' 'bout, Ray. I ain't done nothin' funny.' But the funniest thing to me is... you think she came back here for you... That's what's fucking funny!” The “bug-zapper” humorously emits its incongruously appropriate and inappropriate noise just as Marty concludes his angry, jealous speech, poking fun at the character, campy films with thunder and lightning emphasizing characters' dramatic lines and the film itself, with its budgetary limitations and ostensible lack of scope.

After having a finger broken by his wife in an ugly front-yard confrontation—masterfully captured with a racing, fevered camera—Marty seeks out the man he hired to follow Ray and Abby, sleazy private investigator Loren Visser (played with villainously cretinous relish by a superb M. Emmett Walsh). Visser is the Coens' first outsider—less so in terms of his geographical and cultural identity and more so in his complete lack of moral boundaries (the theme would become increasingly literalized in the Coen canon, culminating with the angel from hell, or at least some foreign country, Anton Chigurh, in No Country for Old Men). Visser is fat and sweaty with a devilish cackle and scaly, clammy features. Flies buzz around and about his face. Several of the best scenes in the entire Coen filmography are of Marty and Visser conversing, each holding the other in contempt as they go about their unseemly business. A terse, funny exchange buttresses the Coens' sensibility and interest. Marty: “I got a job for you.” Visser: “Well, if it's legal, and the pay's right, I'll do it.” Marty: “It's not strictly legal.” Visser: “Well, if it pays right, I'll do it.”

In its noirish iconography and air of morbidity, Blood Simple foreshadows the Coens' future efforts. Small-town Americana is the frequent home to Coen narratives, with its seemingly limpid innocence and relative tranquility being brutally invaded by outside forces, always unleashed by their bosses who egomaniacally call the shots behind their big desks—a Coen motif, from Nathan Arizona played by Trey Wilson unwittingly unleashing Leonard Smalls in Raising Arizona to Jerry Lundegaard played by William H. Macy hiring Carl and Gaear to kidnap his own wife in Fargo to the crooked businessman in No Country for Old Men embodied by Stephen Root letting out the demon. In each case, and others, the man behind the big desk believes he can control his fate, and in every instance, the weapon they let loose proves to be uncontrollable. Often, they are even killed by the very demon they let out of the box. The crushing absence of empathy for others informs the Coens' fiendish rogues gallery. Like those who would follow him in the Coens' art, Visser is a serpentine phantasm, putting about in his Volkswagen Beetle. The exchange between Marty and Visser encapsulates what would be re-imagined in Police Chief Marge Gunderson's famed tabulation in Fargo: counting the victims, she concludes, “And for what? For a little bit of money. There's more to life than money, ya know. Don'tcha know that?”

For Visser, like Peter Stormare's coldblooded sociopath, however, the temptation of money is too great to resist. Which is what, in part, separates the voracious, beastly outsiders from the people who are victimized by their own bad luck and poor choices. Ray and Abby are unable to enjoy one another's company, as Marty successfully plants the seed of distrust in Ray's mind. Everything flows from that; and as Ray finds himself covering up a crime he believes Abby has committed, he becomes the most plaintive character of Coen sagas. Like H.I. McDunnough in Raising Arizona, and Tom Reagan in Miller's Crossing, and Llewellyn Moss in No Country for Old Men, each character loses a piece of their soul in sacrificing for those they love, in one way or another. In this picture, Ray and Abby misconstrue one another's motivations and hearts. Finally, when pressed by Ray, Abby states, “I don't know what you're talking about, Ray. I ain't done anything funny,” just as Marty predicted.

Symbolism and representation is to be found in Blood Simple's thematically rich visual subtext. Acknowledging the influence of Roman Polanski and specifically his The Tenant in crafting the horror of the nearly abandoned hotel in Barton Fink, Blood Simple's use of four rotting fish may be an homage to the Polanski picture Repulsion, in which a decaying rabbit mirrors the psychological state of the protagonist. The fish in Blood Simple fester and spoil with greater alacrity just as the film's storyline spirals out of control for all of the characters. In two perfectly corresponding shots, a flock of birds at a roadside lift off to the air, and, in the next shot, their cumulative shadow splashes against the road's morning daylight. Ceiling fans—one of which hypnotizes Marty, who appears to be dead in his chair as he stares at it—accentuate the film's sense of insularity and loneliness, as the devices connote futility and fatalism in the overpowering face of the oppressive Texas heat. The Coens use windows to communicate the naivete and contrasting innocence of Ray and Abby, whose windows are never curtained or covered as Visser watches them couple and sleep together. The windows of an apartment purchased by Abby appear like two gigantic, watchful eyes. Ray realizes only too late how feckless the two have been (“No curtains on the windows,”) as he stares out into the night through Abby's enormous windows.

Carter Burwell's simple, eerily repetitious score starkly conveys the picture's insidious tension and sense of overarching doom. The Coens' gripping aesthetic control—which was yet another sign of things to come—finds itself expressed in the glide of the camera, such as when it flies through a bar, and hovers upward to avoid a motionless drunk. In the film's most widely noted scene, a man crawls on the unforgiving hard pavement of a road, illuminated by passing headlights. Once again “The Road” becomes paramount as the wounded man continues to struggle, his body convulsing as he spews blood. Isolation, most recently revisited in No Country for Old Men, seems to close off the participants of the tale, so that the whole world in all of its moral and recondite complexity is reduced to a single series of events, which, as always in the Coen universe, seem equally predetermined and manipulated. As in their later work, Blood Simple offers the explanation that seems the most logical: choice results in what is frequently labeled “destiny”; chance and fate are acolytes of cognizant decisions. This makes the Coens more interesting than the behaviorist scientists they are often described as being (which is, as far as it goes, accurate). Ray may believe the worst about Abby but he chose to let Marty into his head; he chose to dispose of Marty on behalf of Abby; he chose to not alter his personality so much as to clearly explain what transpired during one of the film's most eventful evenings. People are who they are, the Coens freely admit—but their choices determine what they are. Javier Bardem's psychotic killer in No Country for Old Men chooses fate to be his idol, his golden calf, so by the end of the story it has chosen him.

Like the somewhat pitiable but whimsically fanciful H.I. in Raising Arizona describing the background of his relationship with Ed, or the corporate mountebank in The Hudsucker Proxy, or Sam Eliot's rambling, forgetful “The Stranger” in The Big Lebowski, or Ed Crane in The Man Who Wasn't There—whose titular distinction makes his narration questionable at the outset—or Sheriff Ed Tom Bell in No Country for Old Men, who confesses to Carla Jean Moss that his mind wanders, Blood Simple's narrator, the reptilian Visser is not to be trusted. In each case, their recollection of events or perspective of the same is severely limited. Indeed, each character seems to romanticize and nearly fetishize certain aspects of the events, or people, or places, about which they are speaking. Which, the Coens seem to gently remind the viewer, is only natural.

This narration, however, is predominantly limited in its usage, and is intrinsically a doorway through which the Coens seamlessly articulate the diverging portraitures of the world known, in which evil is inexplicable in almost all ways but its avarice (money is, after all, at the heart of the Coens' stories, the motivating force for the unscrupulous), and the world of the mind. The Coens' characters are endlessly fixated on better places, happier times and idyllic havens. Voiced by Johnny Caspar (Jon Polito) in Miller's Crossing, the Coens are, not esoterically, but defiantly, almost contumaciously, fascinated by the “morality and ethics” into which they repeatedly delve. The Coens' comprehensive interest in these themes, however, does not reduce matters to mere abstract philosophical concepts. Finding a more Aristotelian vein in which to survey these considerations and quandaries, the Coens are not interested in presumptuously crafting an artistic equivalent to Descartes' call for a rationalist revolution or Locke's insistence on creating a “moral algebra,” by which all problems of morality would be reduced to calculations of abstract formulas. There is a consistency to the Coens' compilation, but both the consequences and evaluations (judgments, though not incorrect, is probably too loaded a term) are not predestined. Successive good characters either perish or are wretchedly tormented in the Coens' embroidery, and many evil ones seem almost invincible, but for unforeseeable circumstance, or seeming mischance, or possibly plain bad luck. Yet which is which, and who is to say what shapes events on earth? Abby believes it is Marty, or an avenging ghost of Marty, stalking her in the film's final sequence, completely unaware of the truth. H.I. manages to pull a grenade pin, perhaps by accident, as Smalls punches him away. Marge follows through on a hunch because of an old friend's lies, and then stumbles on one of the perpetrators disposing of his accomplice. In The Ladykillers, G.H. Dorr and his colleagues are flicked away as though they are ants annoying God. Chigurh had his eyes off the road at the worst possible time. In each case, the killers and criminals have largely already triumphed or failed in their objective (usually succeeding insofar as their original scheme goes, only to encounter greater asperity and trouble).

In Blood Simple's taut denouement—the final movement between McDormand's Abby and Walsh's Visser—the Coen predisposition becomes evident, and speaks volumes about their cinema. Like the scene in which Smalls kills little, harmless creatures (“He was especially cruel to little things,” H.I. tells the viewer, as he seems to have manufactured Smalls out of a nightmare), and especially the horrifying scene in which Carl and Gaear nonchalantly break into the unsuspecting Mrs. Lundegaard's home, and Anton Chigurh confabulating with Carla Jean in her own home, the chimerical meets the quotidian, the poisonous shadows the obedient and kindhearted. Blood Simple is charged, eccentrically meticulous filmmaking—precise and loose, focused and in disarray all at once. The Coens' affinity for marrying the most apparently antithetical properties to one another—tragedy and quirkiness, fear and amusement, the anagogic and the everyday—may very well stem from the very texture of their cinematic dissertations on the conflicting characters they observe. Like the all-powerful dirty money in No Country for Old Men, which seems to corrupt all who cross its path, the efficacy of the Coens' more mature filmic disquisitions is arrestingly potent, luring the viewer like Marty's little illicit offering to Mr. Visser.

72 comments:

Still my favorite Coen, Blood Simple is their funniest, most savage picture. They hadn't mastered that prototypical Coen polish and art-distance yet, and that, while I really like most of their pictures, is a good thing here. Burn After Reading, one of the best pictures of last year, and predictably underrated, was a return to this wilder-woolier nature, only with the master-crafsmanship. Win Win!

Yes, Chuck, our mutual love for Blood Simple can always make us feel good on a blue day. I agree that there is an intimacy with Blood Simple that is completely singular, despite all of the foreshadowings to future great things for the Coens in it. Thanks for the comment!

I don't have the list of Best Supporting Actor nominees for that year staring me in the face, but I think Walsh should have been nominated. He's not in the film much but he makes every last second of his appearance count for everything.

This is some of the best writing on ANY Coen movie I've EVER read. Alexander, I really like you how threaded many of the themes through the Coen filmography and made some very intelligent and philosophical points. Remarkably written and very well thought out.

I happen to love BLOOD SIMPLE myself. I think it is one of the best neo noirs of them all and Mr. Walsh gave one of the best performances of all neo noirs as the commpletely bad man.

Any other Coen pieces you've written?

Thank you for the very kind words, Anonymous. I agree that Blood Simple is a fine neo-noir and, naturally, the Coens' first foray into playing with genre expectations. And we agree about M. Emmett Walsh, who is truly quite perfect in this film.

Yes, I have written another essay on the Coens; it was for Burn After Reading, approximately six months ago.

Thank you once again for the effusively kind comment.

"The film begins with melancholic, almost rueful, narration, visually matched with shots of a long, barren and desolate Texas road."

"The camera, fluid but controlled, focuses on doors, particularly at nighttime, heightening the palpable fear of who or what is lurking behind them."

"An emphasis on the patulous Texas outdoors pervades the film, contrasted and juxtaposed with the stifling, closed interiors in which people struggle. Shots of cowboy boots populate much of the picture. Blood is found on the ground with great regularity."

"The picture, photographed with blue-tinted deliriousness by Barry Sonnenfeld, is laced with an oneiric imperishability of location and personage, which meticulously creates a moony pattern that courses through the picture—and the Coen oeuvre entire."

"Ceiling fans—one of which hypnotizes Marty, who appears to be dead in his chair as he stares at it—accentuate the film's sense of insularity and loneliness, as the devices connote futility and fatalism in the overpowering face of the oppressive Texas heat."

"The windows of an apartment complex purchased by Abby appear like two gigantic, watchful eyes."

"Carter Burwell's simple, eerily repetitious score starkly conveys the picture's insidious tension and sense of overarching doom."

"The Coens' affinity for marrying the most apparently antithetical properties to one another—tragedy and quirkiness, fear and amusement, the anagogic and the everyday—may very well stem from the very texture of their cinematic dissertations on the conflicting characters they observe."

In a review of astounding insights and an all-inclusive examination of the filmmaking of the Brothers Coen, I listed my personal favorites above. This is quite simply the finest and most intellectually stimulating review this film has ever received ANYWHERE and from ANYONE. The cynic could contend that this poster is issuing patronage, but one only has to read the essay's unrelenting scholarly brilliance tpo know it's truly a definitive piece. It's astounding length leaves no stone unturned, and there's no question it's a major work of it's irreverent artists, who I will say are "Lynchian" in their unearthing of the seedy underbelly of small-town Americana. Perhaps BLUE VELVET may come to mind, even if he could be reasonably argued that the intentions diverge here.

BLOOD SIMPLE, as Alexander insightfully contends is abundant in "mordant humor" and "razor-sharp wit" and it certainly can be categorized as a "mind-bening" neo-noir.

I love the mentioning of The Road, as a recurring Coen motif, and the concept that the Coens are "more interesting than the 'behavioral scientists' they purport to follow. And that dazzling desceiption of the film's "taut denouement" is simply extraordinary.

For those who really want to examine this film from a philosophical vantage point, try THIS on for size:

"The Coens' comprehensive interest in these themes, however, does not reduce matters to mere abstract philosophical concepts. Finding a more Aristotelian vein in which to survey these considerations and quandaries, the Coens are not interested in presumptuously crafting an artistic equivalent to Descartes' call for a rationalist revolution or Locke's insistence on creating a “moral algebra,” by which all problems of morality would be reduced to calculations of abstract formulas."

I have no words, other than to plead with all serious film lovers to avail themselves of this exceedingly brilliant film criticism. I like that reference to Polanski's THE TENANT too.

FARGO is my personal favorite Coen film, but this is definitely near the top.

Well, thank you very much, very sincerely, for that astoundingly kind and warm comment, Sam. I'm touched.

Fargo is not one to be argued with as a favorite for the Coens. Certainly one of their best.

I almost used that same term, Sam, "Lynchian"--but part of me wonders if it shouldn't be the other way around, as Blue Velvet arrived a little bit after Blood Simple, haha. Thank you so much for making that connection, however!

Blood Simple is an arresting, intoxicating picture, though, and I'm happy to hear you found this piece so rewarding, Sam. Thank you once again--as is often the case, I'm simply overwhelmed!

I have no words Alexander.

But I think my favorite part of your post is the connection to this and NO COUNTRY FOR OLD MEN. What do you think of that?

Thank you, Harold.

Well, there are myriad connections to No Country for Old Men and Blood Simple. I saw No Country as the film through which the Coens went "full circle," so to speak, in practically every manner of speaking. The locations, the milieu, the atmosphere, the visual touchstones, the ceiling fans, and one of my favorites: the blood.

The blood on the ground in No Country for Old Men may describe as well as anything how the Coens have artistically matured since Blood Simple. In their debut, it helps mark where violence has taken place, and there is of course a dream sequence in which Abby sees Marty spewing a seemingly limitless supply of blood onto the floor.

In No Country, it's made richer by the connection to the geography (so much of the blood is drying against the "hard... soil," as one character later calls it) and, fittingly, the money at the film's heart. The trail of blood at the beginning leads Moss to the money--and as he takes the money, a trail of blood follows him. Later, Chigurh tracks him with his own blood. One could interpret the final scene of Chigurh as where he, handing over a bloodstained one hundred dollar bill to a kid, allows another trail of blood to lead others to the money. The money is literally signposted, marked and evidenced by the presence of blood. It could risk becoming excessively simplistic (blood money) but the Coens use the motif just sparingly enough so that it doesn't become intensely obvious.

There are many parallels, however, and all are quite interesting to look into.

Wow! Sam Juliano speaks the truth. I've never seen such a tremendous piece on this film before. I saw it once some years back and thought it was good. Now I need to see it again.

Beautiful essay, Alexander.

Thank you, Tim. I hope you seek the film out once again. It's a winner and benefits significantly from repeated viewings. It gets better with each one for me personally.

I love this movie! I had to print your piece out because I'd have eyestrain if I read it on the screen but thank you for writing this detailed and very smart piece.

Fantastic review, Alexander. Your grip on the Coens has always impressed me, but then you always impress me at every turn. I'm a fan of this film too. My favorite Coen is No Country for Old Men but Fargo, Raising Arizona and Blood Simple are not far off. Then there's Miller's Crossing and Barton Fink. What a great career they've had.

By the way Anton Chigurh and Loren Visser are two of the best villains ever! And I should know because I'm Dr. Death.

Thank you very much, Dr. Death. I'm glad you avoided suffering from eyestrain in reading my piece.

Moses, thank you very much for the kind words as well. The Coens do indeed have an impressive catalogue of films.

Well, well, well...

You've done it again, Alexander. I've only been a patron of the blog for a few months, but I am a better film-goer because of it. I love this piece:

"In its noirish iconography and air of morbidity, Blood Simple foreshadows the Coens' future efforts. Small-town Americana is the frequent home to Coen narratives, with its seemingly limpid innocence and relative tranquility being brutally invaded by outside forces, always unleashed by their bosses who egomaniacally call the shots behind their big desks—a Coen motif, from Nathan Arizona played by Trey Wilson unwittingly unleashing Leonard Smalls in Raising Arizona to Jerry Lundegaard played by William H. Macy hiring Carl and Gaear to kidnap his own wife in Fargo to the crooked businessman in No Country for Old Men embodied by Stephen Root letting out the demon. In each case, and others, the man behind the big desk believes he can control his fate, and in every instance, the weapon they let loose proves to be uncontrollable. Often, they are even killed by the very demon they let out of the box. The crushing absence of empathy for others informs the Coens' fiendish rogues gallery. Like those who would follow him in the Coens' art, Visser is a serpentine phantasm, putting about in his Volkswagen Beetle. The exchange between Marty and Visser encapsulates what would be re-imagined in Police Chief Marge Gunderson's famed tabulation in Fargo: counting the victims, she concludes, “And for what? For a little bit of money. There's more to life than money, ya know. Don'tcha know that?”"

It's one of my all time favorite neo-noir films and the catalyst for unfortunate events (this speaks specifically to noir, too) is evident, as you point out, in all of the Coens' films: money.

I love how you link these Coen Bros. films in the quoted section above and how they all have a distinct character type who unleashes the entity that will mete out death. "Fargo" and "No Country" definnitly fdall into this category, but where I think they excell is in how they deal with these super-serious postmodern themes (Margie is the modernist, asking "and for what?" and Chigurh is the ultimate nihilistic monster that exists in a postmodern world); they seem much more in control of the conventions and the heavy themes and are much more comfortable going for subtle comedic moments admist mayhem....because like Sherrif Ed Tom Bell says in "No Country", sometimes all you can do is laugh. The irony of the unleashers being killed by those they unleash is, as you so astutely state, some of the best comedy in how these business types think they can control what is uncontrollable. The Coen's seem to have a lot of fun with that motif.

If the Coens are at their most mature with the aforementioned films, than I think you can definitely see that brilliance in the early films you've mentioned along with "Blood Simple". Where "Blood Simple" (and "Raising Arizona" for that matter) is still dipping it's toe into the pool, "Fargo" and "No Country for Old Men" are swimming with ease in the deep end.

All of that said, The early Coen films are dearest to my heart, and even though the newer stuff may be more controlled and nuanced aesthetically speaking, the early stuff is what I'll always remember most. The scene in "Blood Simple" where M. Emmet Walsh just can't seem to clean up the blood as it just keeps coming and seeping....it's amazing thinking about that image now and the image (and symbol) of Chigurh, always coming, always seeping into our daily lives waiting to turn our world upside down and into a nightmare.

Anyway, sorry for the rambling thoughts, I'm reading this and commenting and I just got home from San Francisco like an hour ago (it's about a 12 hour drive for me) so I'm a little tired and somewhat sleep deprived, but I saw this when I checked the blog for updates on my phone today and I just had to read it.

Great work. More thoughts later, I am sure of that (and on "Watchmen", too as I look to write up a review on that tomorrow after some much needed sleep. Haha.).

Thank you for the fantastic comment and very kind words, Kevin. As always, much appreciated. I'm truly humbled by your first statement in particular!

Yes, these themes do recur over and over with the Coens, and for me, when I watched No Country for Old Men for the very first time, one of the (million) things going through my head was, "This is it. This is the consummation of everything these two have done." Ironically, of course, it was based on Cormac McCarthy's novel--but that somehow makes sense, as it's frequently when directors turn outward that they find the most ultimately personal resonance. No Country for Old Men is a definitive example of that.

I completely agree with your point that one of the more blackly humorous aspects of the Coens' pictures is the recognition that the apparent piranha behind their big desk cannot keep the leash on those who are designed to "mete out death," as you so aptly describe them. Indeed, as you agreed with my piece--they're often exterminated by the very beast they let loose.

That is an excellent point about Sheriff Ed Tom Bell in No Country saying that all you can do--which is a fine defense of the Coen perspective, which can take these matters quite seriously at one moment, only to recognize the (often sad or dark) humor that accompanies it as another part of life.

And yes, as it should be plain by now, the Coens' films are concerned with the tempting allure of money. Particularly its relationship with small-town Americana.

That's a fabulous description of Chigurh turning our world into a nightmare. Like Marge, Ed Tom Bell just can't understand it. Blood Simple's characters don't, either.

Great to hear you were in my area! Take it easy now, and thank you once again. I look forward to whatever future thoughts you bring.

Stimulating and fascinating essay, Alexander Coleman. I'm always amazed and dazzled by your keen insights and beautiful writing.

The morality in the Coens stories is interesting. Must keep thinking about this.

Thank you, Ben.

Thinking about this in the shower this morning, I considered the idea that Blood Simple tells the story of punishment for a man and woman (wife) who do make the mistake of committing adultery. Contrasting them with H.I. and Ed in Raising Arizona and Marge and Norm in Fargo, especially, one sees how the Coens view marital relationships as stronger, warmer and vastly more unbreakable than one like Ray and Abby's here. Only in The Man Who Wasn't There adultery once again makes a marriage gangrenous; and in No Country for Old Men the husband is punished at every turn for, according to Chigurh's "code," placing himself and the money above his own wife. It's another intriguing avenue to explore.

Exquisite and evocative piece, Alexander. Tremendously organized and considered. Downright mind-blowing.

Wow, Alexander. I'm flabbergasted at how good this review is. You've achieved a parity with Matt Zoller Seitz's amazing review of No Country from The House Next Door, which I previously considered the best essay on a Coen brothers film (and in microcosm, the Coens themselves) ever written. I love how you've used other Coen brothers' films to point out the detailed nuance and thematic value of Blood Simple as an individual entity and as an important touchstone in relationship to their overall body of work.

Brilliant, sir, just plain brilliant.

Your review is beautiful and I have little to add, but you've illuminated elements I never considered before, especially your insightful connections to Roman Polaski.

I've always loved the fact that Blood Simple is the Coen brothers' most O'Henry-esque story, in which all the characters make poorly-conceived assumptions about each other and then act upon them, each being destroyed by their own ignorance and loathing for the others. Only Ray acts out of a sense of love and compassion but ends up questioning all his actions when he (inaccurately) suspects Abby in the end. All of this is crowned with a vicious bit of black humor when Visser realizes how distorted everything has become at the very end, his cackling laugh a punctuation on the final twist that confirms the dark irony of the entire film.

M. Emmet Walsh most assuredly deserved every Best Supporting Actor award that year but as I recall, he received little reward for his career-defining performance. He is excellent in Blood Simple, turning an ugly character into something memorable and horribly wonderful. It's the kind of virtuoso character acting that a Peter Lorre or Claude Rains did in their heydays.

I think Blood Simple is quite simply a masterpiece but I do think that No Country represents the Coens brothers' achievement as directors in that the two films bookend their maturation as filmmakers and show how ably the Coens now work the medium. The two films share a host of details and themes, but in No Country the brothers have let go of many of the showier directorial tricks that drove their early work and proved how deftly they can tell a story. While I love all the curious camera angles and tricky moves of Blood Simple, all of these elements tend to remove one from the picture by drawing so much attention to themselves. In No Country, the artistry is still there (and in fine form no less) but the storytelling is much more refined, more subtle, and ultimately more effective.

Awesome job, my friend. You did not disappoint. I think a Coen brothers mini-festival is needed now.

Great stuff here Alexander. I recall watching this on VHS after it came out and being happily impressed, especially with Walsh and the show-offy bullet holes of light. I literally haven't seen it since but remember every moment like I have. I also love Hedaya in the film.

Thank you very much, mc, Joel and Christian. All I'll say to the compliments is I'm as humbled as ever.

Christian, yes, once you've seen Blood Simple, I don't think you can forget it. So many highly memorable moments and images, such as the ones you mention. I love the bullet holes! Hedaya is absolutely great as well in perhaps the film's most challenging role.

Joel, thank you for the highly kind words about writing about this film specifically and simultaneously tying it to the Coen canon entire. I considered it a tricky endeavor but I'm pleased it turned out okay. :)

Sincerely, thank you for the effusively warm remarks. I know you love them Coen boys, so I hoped I wouldn't disappoint you.

Joel, I love your point about how O'Henry-esque Blood Simple is. None of the characters know as much as they think they do, and their intertwined fates are determined by the lack of knowledge, and lack of communication, that dooms them (though ironically it is Abby, the most clueless character, who manages to survive).

Great point about Walsh not receiving the wrenchingly deserved accolades that year, and how it's the kind of role a Peter Lorre of Claude Rains (both of whom could play suave and smooth exceptionally well, too) would flourish in. Walsh, though truly owns it and makes it his own. (Is it true the Coens wrote the role with him in mind? I believe I read that somewhere.)

As for your considerable point about No Country for Old Men demonstrating the Coens' assured, stunning maturity (which, comparing aside, and relativity aside, Blood Simple is a great example of, too, especially for a debut work by 20-something filmmakers), I couldn't agree more, Joel. If Blood Simple is a masterpiece, then No Country for Old Men is a formal chef-d'oeuvre, crafted with such precision and penetration that it is nothing less than stunning. It is the Coens' most robustly confident filmmaking of their career... Blood Simple can be viewed as the first great step to it, and naturally, someday down the road, it may stun us to see just what No Country led to.

The ending with Visser letting out that cackle gets me every time. And then the little droplet falling as his expression changes to horror. Gravity in action; cause and effect--a great, concise, perfect visual description of the Coens' art, actually.

I've seen it mentioned that the role was written for Walsh but never in the context of a direct quote from the Coen brothers themselves. It seems improbable and somewhat presumptuous for them to have done that, considering all the ridiculous lengths they went to just to get funding for this film and the fact that beyond some technical work on other small indies neither had any experience to speak of.

Walsh was an established character actor with a long list of supporting roles in a variety of films and TV (over 100 parts by 1984) by the time the Coens started working on Blood Simple. It's possible although I'm guessing they got Walsh and then tweaked the character to fit him.

Thank you for that very informative and detailed response, my friend. I agree--it seems presumptuous, though it's very possible that the Coens were hoping against hope that they could cast the veteran character actor for the part and their dream came true.

Humorously, two evenings ago I watched The Jerk and could not stop laughing at Walsh's robust little performance as a raging madman who randomly chooses to kill Steve Martin's gas attendant.

I also recently saw him (about two weeks ago) in the Mickey Rourke-starring The Pope of Greenwich Village from the same year as Blood Simple in a tiny role as a questioning cop.

Great, underrated character actor. This is certainly his finest hour, though.

Every time I'm caught in an absurdly-similar situation, I can't help but remember that scene from The Jerk with Walsh as the crazed psycho.

"He hates the CANS! Stay away from the cans!"

Oh my god, that kills me just thinking about it.

It's possible they did write the scene for Walsh. It goes right along with the stories of Tarantino scripting Larry specifically for Harvey Keitel, winning Keitel over with his writing, thus ensuring his first feature got off the ground.

As they say, truth is often stranger than fiction.

Of course, I'm speaking of Reservoir Dogs.

Indeed you are (speaking of Reservoir Dogs).

You're right, in Hollywood truth is often stranger than fiction.

That "He's shootings the cans! He hates the CANS!" bit is quite hilarious. Hahaha.

OK, I think I mispoke when I said "all the characters make poorly-conceived assumptions about each other." In reality, Marty's only mistake is that he thinks he can trust Visser. It generally fits my comment, but it's not the deliberate sort of misjudgment I was getting at.

Having just revisited the film once again, I'm haunted by the score and also reminded how attractive Francis McDormand was in this film. I also must commend the work of John Getz, who was quite excellent as the hapless Ray. The scene where he must address Marty's fate is by far one of the most disturbing and tense things I've ever seen.

Gotta love the shades-of-Lady-Macbeth backseat in Ray's car too.

And the flies that keep buzzing Visser's head throughout the movie, as though he stinks so badly of moral decay that the insects can't leave him alone.

One thing I noticed is that the bug zapper punctuation that you mentioned in your review must be a special effect. It actually happens on camera, in the corner of the shot. It's so perfectly timed that it couldn't have been an accident, so I can only imagine someone out-of-frame tossed something into the zapper at that moment. Brilliant.

One last observation: Do you think the Coens were mocking Blood Simple when they put The Big Lewbowski's blissfully unaware PI (played by Jon Polito) in a VW Bug as well? I kinda love the weird juxtaposition, but it does seem ripe for parody. It's almost silly to think a true Texan like Visser, so equally fascinated and disdainful of Commies, would even consider driving a VW Bug, yet it kinda fits his low-rent style.

As wonderfully rough-around-the-edges and unrestrained as this film is cinematically, I really love it for it's gritty style and (attempted) directorial precision. as you say, it certainly "demonstrably essays the Coens' obsessions and idiosyncrasies, their fixations and concerns."

I nearly brought up the Volkswagen Beetle appearing in The Big Lebowski in this piece, but decided it was unnecessary and for those who are deeply into the Coens, they'd know that, anyway. I think there is a connection between the films. The Big Lebowski is in some ways the ultimate auteur send-up (for the Coens)--in that it actually somewhat stingingly pokes fun at their themes, interests and their work.

I agree that the VW Beetle seems to be a bizarre choice, especially for a private-eye. I think it's something of a send-up of the smooth PI image we usually think of when we consider film noir. There's that wonderful scene where Visser humorously remarks to Marty that that one girl thought Visser was a swinger because of him rolling up a cigarette, believing it to be marijuana. Which fits with the VW Beetle.

I think it's ultimately a big of black humor, and an excellent contrast to what we normally consider obvious for characters of this type. But that's what I love about Visser (among other things)--he's positively crude and, as you say, "low-rent"--in the extreme.

Another thing I nearly included in my piece: notice that same scene of Marty's offer to Visser where Visser actually snuffs out his cigarette with his foot in his car. Every time I watch that scene I picture dozens and dozens of crushed cigarettes on the floor of his car right there. Some may protest that it's all too much, but I'd counter that that is the point: Visser is too much, and he doesn't belong. So, yes, I think the low-rent suitability provides the context for the vehicle, and for that matter it works separately on its own in The Big Lebowski.

Yes, I'm quite certain the "bug-zapper" moment is a special effect (and a wonderful one). The ambivalence it helps to create (partly comic, strangely dangerous) gels with the entirety of the film. Thanks for bringing this up as well.

"Gotta love the shades-of-Lady-Macbeth backseat in Ray's car too." Yep, truly beautiful imagery. I love the matching shot of Maurice pressing a button on his answering machine with Ray dipping his finger into the blood in his backseat. And then the blood becoming visible just as Maurice exits.

Another motif I love is the dead-end street where Marty and Maurice each angrily has to turn around and speed away. In a film about the openness of the region, and the relationship it has to "The Road," Ray seems to live at the dead-end.

I agree with you as well about McDormand looking so attractive in this film. She is of course quite effective in the film. I love the little touches the Coens give Getz. The snort of disbelief, shock, anger and hurt when Abby, having picked up a telephone, says to him, "It's Marty," is simply priceless and one of the film's absolute best moments. (Of which, it should be clear by now, there are many.)

***

As wonderfully rough-around-the-edges and unrestrained as this film is cinematically, I really love it for it's gritty style and (attempted) directorial precision. as you say, it certainly "demonstrably essays the Coens' obsessions and idiosyncrasies, their fixations and concerns."

***

Yes, indeed--to the first part I say I completely concur and to the second part, well, it's always egotistically-soothing and gratifying to have one's words used by others. Thanks so much for contributing so mightily to the discussion, Joel!

First sentence, third paragraph: a bit of black humor. It's late. Probably made more mistakes. :)

Hi! Alexander,

I enjoyed reading your very detailed, descriptive, insightful, review of this 1984 film that is considered a neo noir... you summed it up perfectly!...Thanks,

Alexander, I have watched the 1984 film Blood Simple for the first time maybe 2 or 3 years ago.?!? (Shrug shoulders)

I must admit some "film noiraholic" do consider this film a neo noir and some followers of noir just consider this film a noir.

(Below is a "very condensed" definition of neo-noir and film noir that I have "overheard" and agree with...

...Neo noir: Films that were/are "conscious" of noir elements... done or made in a style that is characteristic of film noir.

Where as on the other hand, the creators, of film noir were "unconscious" of the fact that they were creating the film noir style and using the elements.

For instance, some of the same terms that you used here on your blog to describe the 1984 film "Blood Simple" "dark" human elements that the Coens' were probably "conscious" of, during the making of their 1984 film "Blood Simple," but on the other hand, Jacques Tourneur, probably "wasn't conscious" of, when he created the 1947 film "Out of the Past.")

Actor Robert Mitchum, I think even pointed out the fact, that they were unaware of the fact, that they were creating "film noir" at the time that they were creating what we all now refer to as "film noir" in a book that I own entitled The Big Book of Noir: by Gorman, Server and Greenberg, but I have to check the book again in order to confirm what he(Mitchum) actually said in the book.

Alexander, you wouldn't believe it, but some followers of film noir don't believe that there is a difference between film noir and neo noir

But, I truly think there is a difference between both the films released during the "classic" and the "modern" period(s)of this style of film making referred to as "film noir and neo noir."

Therefore in the end, I must admit that this is one of my favorite Coen's film(s) that is considered a neo-noir and a very well written review by you once again!

Tks,

Dcd ;-D

A terrible headache is keeping me awake!

Dark City Dame, thank you very much for the fantastically detailed and thoughtful comment about this film's standing as a neo-noir and the debates that continue over the use of that term of classification versus simply film noir.

I agree with you that a distinction ought to be made. As with most artistic movements, film noir as it is today commonly understood was not comprehensively conscious in the sense that it would need to be defined with some perspective (which the French so helpfully provided).

I'll have to grab myself a copy of that book from which you pull that quote from Robert Mitchum, Dark City Dame. I have read from interviews of him that he continually made these statements which pointed out that the creators of film noir were themselves not definitively aware of what exactly they were forging. For the most part, the films were classified as crime dramas of one sort or another.

The irony is that a neo-noir like Blood Simple is, as you eloquently state, more "conscious" of the very concept, and idea, and finally transmogrification of "film noir," with the distance it has from the films and literature that inspired it.

I'm glad to hear you like Blood Simple, DCD, and thank you very much for all of the kind words. I don't sleep, as you can see. I'm a vampire.

ALEXANDER!!!!

Omg!...How very apropos...that you mentioned you are a "Vampire" and the title of your review is....

ha!ha!

Dcd ;-D

Ah, didn't think of that one. Haha!

That's quite a review and makes this film worthy of seeking out.

Never knew it was available.

Thanks for your in depth reviews.

Makes film viewing worthwhile! ; )

Cheers!

Alexander said,"I'll have to grab myself a copy of that book from which you pull that quote from Robert Mitchum, Dark City Dame.

I have read from interviews of him that he continually made these statements which pointed out that the creators of film noir were themselves not definitively aware of what exactly they were forging."

Right you are! Alexander, because I'am reading a book now entitled "Death on the Cheap" by author Arthur Lyons'

I must admit that a fellow "noirhead" clued me when it comes to this wonderful book!)and on the back cover is a quote by none other than actor Robert Mitchum, himself...and here goes his quote...actor Robert Mitchum said, "**ll, (expletive) we didn't know what film noir was in those days. We were just making movies. Cary Grant and all the big stars at RKO got all the lights.We lit our sets with cigarette butts."

Dcd ;-D

Hi! C.M.,

C.M. said, (To Alexander and not Dcd) "That's quite a review and makes this film worthy of seeking out. Never knew it was available."

C.M., I was waiting for Alexander, to return before I answered you,(Because this isn't my blog and you were addressing Alexander, directly, and not me!...Oops! I'am so sorry! A.C.) but I will email you,(C.M.) later about this film.

Take care!

Dcd ;-D

Thank you very much, Coffee Messiah. Always good to hear from you. It is most certainly available. :) Thanks again for the kind words.

Thank you for expanding on your earlier comments, Dark City Dame--I love that quote of Mitchum's about the films in which he starred not having sufficient lighting, necessitating the cigarette illumination. Haha! :-)

Hi! A.C.,

Which of course, also led to total darkness, lack of light, and which of course led to shadows that have come to be associated with this wonderful thing called "Film Noir" to a certain extent.

Btw, in a 1947 film noir called Desperate

I think that the light and darkness was used quite effectively, in a scene were the main character (The protaganist, actor Steve Brodie), was being beaten to a "pulp" for lack of a better word... and director Anthony Mann, (or rather his cinematographer, George E. Diskant, I must admit that I had to look up the cinematographer's name.) used a dark room, a swinging light and actor Raymond Burr's face...to "achieve" or "create" what actor Robert Mitchum, didn't know what to call a the time...Film noir.

"to "achieve" or "create" what actor Robert Mitchum, didn't know what to call at (not a) the time...Film noir."

I must leave now A.C. and take medicine for my "terrible" headache.

Take care!

Deedee ;-D

Alexander Coleman, I have been reading your blog for some weeks now and I have to say, it is crystal clear to me that you are a genius.

Will you marry me?

the average person holds ten to twenty pounds of waste in their colon. go to nancypelosi.com to get special pills that will clean the intensines instantly. an all natural chemical enema. warning may cause insanity

Ha ha. If Visser were alive and well today (and who knows, maybe he is?), I'm sure he'd be running a little spam scam on the side to make some extra bucks.

Maybe Ned Valentine is Visser?

Visser is a pisser of a character. Love to hate him so much. Great essay I must say.

Alexander, this is truly a thread for the ages, and your spectacular review deserves ever bit of the celebration here. Kudos again to you Sir! The staggering amount of quality and exhaustive comments speak for themselves.

Anna, I can't make any promises. :)

Hahaha, Joel, good, funny and appropriate point about ned valentine's racket.

Anonymous, thank you; Visser is indeed a "pisser," as you suggest.

Sam, thank you for the kind words, my friend. I'm quite happy to see the strong turnout for this film.

I just watched this one again because of your dazzling piece, Alexander and I have to say you uncovered many layers to it I had never considered before. This movie does amaze me but never as much as it does now. For that I have you to thank.

Thank you very kindly, Moses. But I have you and the other readers to thank for sharing my passion for cinema! Haha.

GREAT piece. Loved reading this during a boring afternoon. I love the part when McDormand stabs the dude's hand with a knife.

Thank you, Anonymous. A memorable moment to be sure.

Hi! A.C.,

I have send you 2 emails...Did you receive them?

Thanks,

Dcd ;-D

i cut off ears noses cut off scrotums and tongues and thats why i should be prez

I love this movie. Awesome look at the Brothers Coen.

Thanks, everyone.

Yes, I did finally receive your emails, Dark City Dame--in other words, I finally just saw them. :-)

I love this flick. One of the best and most underrated movies of the 1980's. Mr. Walsh steals the movie but everyone is just great. And the camera flourishes by the Coens are maybe showoffy but really cool for a movie like this.

Great review, btw.

Thank you, skip. I agree with the sentiment of your post.

I watched this movie this weekend and enjoyed it more when I read your review after seeing it. Good work again, Mr. Coleman

Thank you very much, mc. I greatly appreciate your comment.

Stupendous work, Alexander Coleman.

You should be proud.

Thank you, Anonymous.

This is such a wonderful useful resource that you'll be providing You got so many points here, that's why i love reading your post. Thank you so much!

Nice post, thank you for sharing…

Nice post, thanks for sharing, Gastro Health Meds Nexium - Nexium Online!

Nice post, thanks for sharing, Antipsychotic Med Abilify - Abilify Online!

thanks for sharing, - Stablon Online!

thanks for sharing.... - Sildenafil Citrate Viagra !

I would like to thank you for sharing this great information with us. I am really glad to learn about this because it helps me to increase my knowledge. buy aciphex 20 mg purchase celexa

thanks for sharing... Pain Relief Darvocet-N !

This is the best review i ever read....you explored great philosophical points behind Coens movies.thanks a lot for sharing great information.. hope i expect more like this..

thanks for sharing... Advair Diskus - Advair Diskus !

thanks for sharing... For Heart & Blood Pressure - Plavix !

Post a Comment