“The world is full of complainers. An' the fact is, nothin' comes with a guarantee. Now I don't care if you're the Pope of Rome, the President of the United States or Man of the Year, something can all go wrong. Now go on ahead, ya know, complain, tell your problems to your neighbor, ask for help, 'n watch 'im fly. Now, in Russia, they got it all mapped out so that everybody pulls for everybody else... that's the theory, anyway. But what I know about is Texas, an' down here... you're on your own.”

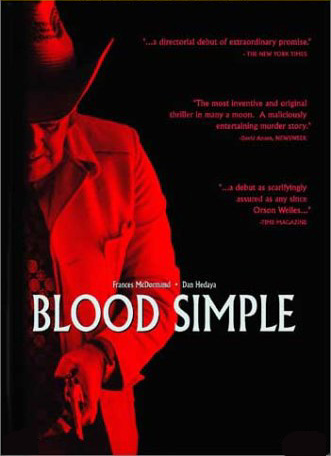

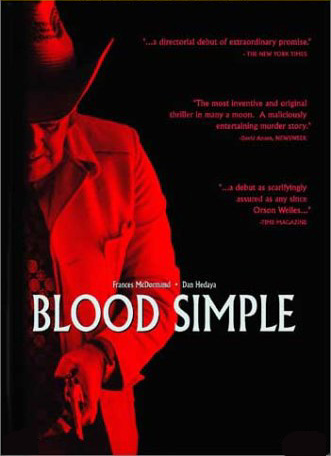

The film begins with melancholic, almost rueful, narration, visually matched with shots of a long, barren and desolate Texas road. Later, characters will dwell underneath ominous ceiling fans, which seem to hauntingly view down upon the hapless. The camera, fluid but controlled, focuses on doors, particularly at nighttime, heightening the palpable fear of who or what is lurking behind them. A blade of light slicing through the darkness underneath a door is snuffed out. An emphasis on the patulous Texas outdoors pervades the film, contrasted and juxtaposed with the stifling, closed interiors in which people struggle. Shots of cowboy boots populate much of the picture. Blood is found on the ground with great regularity. Otherwise decent people make highly unfortunate decisions. An otherworldly creature mercilessly stalks his prey. This, however, is not No Country for Old Men but rather Blood Simple, the 1984 film debut for Joel and Ethan Coen.

Blood Simple is a subtly mind-bending neo-noir crime thriller in which communication is hampered by circumstance and refuge is denied by the apparent intervention of fate. The picture, photographed with blue-tinted deliriousness by Barry Sonnenfeld, is laced with an oneiric imperishability of location and personage, which meticulously creates a moony pattern that courses through the picture—and the Coen oeuvre entire. Characters move through the film like stationary objects pushed, as they are compelled to vacate their respective natural habitats. As will be proven true with their later efforts, Blood Simple demonstrably essays the Coens' obsessions and idiosyncrasies, their fixations and concerns. As a debut, the film is as pure and distilled an introductory declaratory statement as any before or since.

After the film's dry, almost supernatural opening narration, Blood Simple brings its perspective, literally, with Ray and Abby (John Getz and Frances McDormand) driving at night. The road is visible again, and “The Road” will remain a recurring Coen motif. Abby's first line informs where the picture's plot is headed: her possessive husband gave her a .38 handgun as a gift, but she fears she would use it on him if she did not leave him. The camera remains behind Ray and Abby, he behind the steering wheel of his car, she in the passenger seat. The windshield is spattered with rain, which is furiously flung off by the windshield wipers. With each passing car's briefly blinding headlights moving past them, the main cast members have their names flash against the black of night in cool blue.

The Coens' penchant for quirky, offbeat humor—here typically slathered atop the film's laconic dialogue—makes Blood Simple less familiar than its superficially derivative story would suggest. Rooted in the work of James M. Cain, Jim Thompson and other authors of stories about lust and murder, Blood Simple takes on a twisted viewpoint characterized by mordant humor and razor-sharp wit. As Abby's husband, owner of the bar at which Ray works, Julian Marty (Dan Hedaya), confronts Ray in the back of the bar, the Coens use a bug-zapper to simultaneously underline and subvert Marty's dramatic lines. “You think I'm funny, I'm an asshole? No, no, no... what's funny is her... what's funny is, I had you two followed because if it's not you she's sleeping with, it's somebody else... what's funny is when she gives you that look and says, 'I don't know what you're talkin' 'bout, Ray. I ain't done nothin' funny.' But the funniest thing to me is... you think she came back here for you... That's what's fucking funny!” The “bug-zapper” humorously emits its incongruously appropriate and inappropriate noise just as Marty concludes his angry, jealous speech, poking fun at the character, campy films with thunder and lightning emphasizing characters' dramatic lines and the film itself, with its budgetary limitations and ostensible lack of scope.

After having a finger broken by his wife in an ugly front-yard confrontation—masterfully captured with a racing, fevered camera—Marty seeks out the man he hired to follow Ray and Abby, sleazy private investigator Loren Visser (played with villainously cretinous relish by a superb M. Emmett Walsh). Visser is the Coens' first outsider—less so in terms of his geographical and cultural identity and more so in his complete lack of moral boundaries (the theme would become increasingly literalized in the Coen canon, culminating with the angel from hell, or at least some foreign country, Anton Chigurh, in No Country for Old Men). Visser is fat and sweaty with a devilish cackle and scaly, clammy features. Flies buzz around and about his face. Several of the best scenes in the entire Coen filmography are of Marty and Visser conversing, each holding the other in contempt as they go about their unseemly business. A terse, funny exchange buttresses the Coens' sensibility and interest. Marty: “I got a job for you.” Visser: “Well, if it's legal, and the pay's right, I'll do it.” Marty: “It's not strictly legal.” Visser: “Well, if it pays right, I'll do it.”

In its noirish iconography and air of morbidity, Blood Simple foreshadows the Coens' future efforts. Small-town Americana is the frequent home to Coen narratives, with its seemingly limpid innocence and relative tranquility being brutally invaded by outside forces, always unleashed by their bosses who egomaniacally call the shots behind their big desks—a Coen motif, from Nathan Arizona played by Trey Wilson unwittingly unleashing Leonard Smalls in Raising Arizona to Jerry Lundegaard played by William H. Macy hiring Carl and Gaear to kidnap his own wife in Fargo to the crooked businessman in No Country for Old Men embodied by Stephen Root letting out the demon. In each case, and others, the man behind the big desk believes he can control his fate, and in every instance, the weapon they let loose proves to be uncontrollable. Often, they are even killed by the very demon they let out of the box. The crushing absence of empathy for others informs the Coens' fiendish rogues gallery. Like those who would follow him in the Coens' art, Visser is a serpentine phantasm, putting about in his Volkswagen Beetle. The exchange between Marty and Visser encapsulates what would be re-imagined in Police Chief Marge Gunderson's famed tabulation in Fargo: counting the victims, she concludes, “And for what? For a little bit of money. There's more to life than money, ya know. Don'tcha know that?”

For Visser, like Peter Stormare's coldblooded sociopath, however, the temptation of money is too great to resist. Which is what, in part, separates the voracious, beastly outsiders from the people who are victimized by their own bad luck and poor choices. Ray and Abby are unable to enjoy one another's company, as Marty successfully plants the seed of distrust in Ray's mind. Everything flows from that; and as Ray finds himself covering up a crime he believes Abby has committed, he becomes the most plaintive character of Coen sagas. Like H.I. McDunnough in Raising Arizona, and Tom Reagan in Miller's Crossing, and Llewellyn Moss in No Country for Old Men, each character loses a piece of their soul in sacrificing for those they love, in one way or another. In this picture, Ray and Abby misconstrue one another's motivations and hearts. Finally, when pressed by Ray, Abby states, “I don't know what you're talking about, Ray. I ain't done anything funny,” just as Marty predicted.

Symbolism and representation is to be found in Blood Simple's thematically rich visual subtext. Acknowledging the influence of Roman Polanski and specifically his The Tenant in crafting the horror of the nearly abandoned hotel in Barton Fink, Blood Simple's use of four rotting fish may be an homage to the Polanski picture Repulsion, in which a decaying rabbit mirrors the psychological state of the protagonist. The fish in Blood Simple fester and spoil with greater alacrity just as the film's storyline spirals out of control for all of the characters. In two perfectly corresponding shots, a flock of birds at a roadside lift off to the air, and, in the next shot, their cumulative shadow splashes against the road's morning daylight. Ceiling fans—one of which hypnotizes Marty, who appears to be dead in his chair as he stares at it—accentuate the film's sense of insularity and loneliness, as the devices connote futility and fatalism in the overpowering face of the oppressive Texas heat. The Coens use windows to communicate the naivete and contrasting innocence of Ray and Abby, whose windows are never curtained or covered as Visser watches them couple and sleep together. The windows of an apartment purchased by Abby appear like two gigantic, watchful eyes. Ray realizes only too late how feckless the two have been (“No curtains on the windows,”) as he stares out into the night through Abby's enormous windows.

Carter Burwell's simple, eerily repetitious score starkly conveys the picture's insidious tension and sense of overarching doom. The Coens' gripping aesthetic control—which was yet another sign of things to come—finds itself expressed in the glide of the camera, such as when it flies through a bar, and hovers upward to avoid a motionless drunk. In the film's most widely noted scene, a man crawls on the unforgiving hard pavement of a road, illuminated by passing headlights. Once again “The Road” becomes paramount as the wounded man continues to struggle, his body convulsing as he spews blood. Isolation, most recently revisited in No Country for Old Men, seems to close off the participants of the tale, so that the whole world in all of its moral and recondite complexity is reduced to a single series of events, which, as always in the Coen universe, seem equally predetermined and manipulated. As in their later work, Blood Simple offers the explanation that seems the most logical: choice results in what is frequently labeled “destiny”; chance and fate are acolytes of cognizant decisions. This makes the Coens more interesting than the behaviorist scientists they are often described as being (which is, as far as it goes, accurate). Ray may believe the worst about Abby but he chose to let Marty into his head; he chose to dispose of Marty on behalf of Abby; he chose to not alter his personality so much as to clearly explain what transpired during one of the film's most eventful evenings. People are who they are, the Coens freely admit—but their choices determine what they are. Javier Bardem's psychotic killer in No Country for Old Men chooses fate to be his idol, his golden calf, so by the end of the story it has chosen him.

Like the somewhat pitiable but whimsically fanciful H.I. in Raising Arizona describing the background of his relationship with Ed, or the corporate mountebank in The Hudsucker Proxy, or Sam Eliot's rambling, forgetful “The Stranger” in The Big Lebowski, or Ed Crane in The Man Who Wasn't There—whose titular distinction makes his narration questionable at the outset—or Sheriff Ed Tom Bell in No Country for Old Men, who confesses to Carla Jean Moss that his mind wanders, Blood Simple's narrator, the reptilian Visser is not to be trusted. In each case, their recollection of events or perspective of the same is severely limited. Indeed, each character seems to romanticize and nearly fetishize certain aspects of the events, or people, or places, about which they are speaking. Which, the Coens seem to gently remind the viewer, is only natural.

This narration, however, is predominantly limited in its usage, and is intrinsically a doorway through which the Coens seamlessly articulate the diverging portraitures of the world known, in which evil is inexplicable in almost all ways but its avarice (money is, after all, at the heart of the Coens' stories, the motivating force for the unscrupulous), and the world of the mind. The Coens' characters are endlessly fixated on better places, happier times and idyllic havens. Voiced by Johnny Caspar (Jon Polito) in Miller's Crossing, the Coens are, not esoterically, but defiantly, almost contumaciously, fascinated by the “morality and ethics” into which they repeatedly delve. The Coens' comprehensive interest in these themes, however, does not reduce matters to mere abstract philosophical concepts. Finding a more Aristotelian vein in which to survey these considerations and quandaries, the Coens are not interested in presumptuously crafting an artistic equivalent to Descartes' call for a rationalist revolution or Locke's insistence on creating a “moral algebra,” by which all problems of morality would be reduced to calculations of abstract formulas. There is a consistency to the Coens' compilation, but both the consequences and evaluations (judgments, though not incorrect, is probably too loaded a term) are not predestined. Successive good characters either perish or are wretchedly tormented in the Coens' embroidery, and many evil ones seem almost invincible, but for unforeseeable circumstance, or seeming mischance, or possibly plain bad luck. Yet which is which, and who is to say what shapes events on earth? Abby believes it is Marty, or an avenging ghost of Marty, stalking her in the film's final sequence, completely unaware of the truth. H.I. manages to pull a grenade pin, perhaps by accident, as Smalls punches him away. Marge follows through on a hunch because of an old friend's lies, and then stumbles on one of the perpetrators disposing of his accomplice. In The Ladykillers, G.H. Dorr and his colleagues are flicked away as though they are ants annoying God. Chigurh had his eyes off the road at the worst possible time. In each case, the killers and criminals have largely already triumphed or failed in their objective (usually succeeding insofar as their original scheme goes, only to encounter greater asperity and trouble).

In Blood Simple's taut denouement—the final movement between McDormand's Abby and Walsh's Visser—the Coen predisposition becomes evident, and speaks volumes about their cinema. Like the scene in which Smalls kills little, harmless creatures (“He was especially cruel to little things,” H.I. tells the viewer, as he seems to have manufactured Smalls out of a nightmare), and especially the horrifying scene in which Carl and Gaear nonchalantly break into the unsuspecting Mrs. Lundegaard's home, and Anton Chigurh confabulating with Carla Jean in her own home, the chimerical meets the quotidian, the poisonous shadows the obedient and kindhearted. Blood Simple is charged, eccentrically meticulous filmmaking—precise and loose, focused and in disarray all at once. The Coens' affinity for marrying the most apparently antithetical properties to one another—tragedy and quirkiness, fear and amusement, the anagogic and the everyday—may very well stem from the very texture of their cinematic dissertations on the conflicting characters they observe. Like the all-powerful dirty money in No Country for Old Men, which seems to corrupt all who cross its path, the efficacy of the Coens' more mature filmic disquisitions is arrestingly potent, luring the viewer like Marty's little illicit offering to Mr. Visser.